The internet today is a seamless fabric of information, woven so tightly into our daily lives that we rarely pause to consider the mechanism that stitches it together: the search engine. We type (or speak) a query, and within milliseconds, the world’s knowledge is organized, ranked, and delivered. But this seamless utility is the result of decades of chaotic innovation, brutal corporate warfare, and complex mathematical evolution.

To understand where we are going—specifically, the paradigm-shifting arrival of AI Overviews—we must understand where we came from. The evolution of search engines is not just a history of technology; it is a history of human behavior, intent, and the quest to organize the chaos of the World Wide Web.

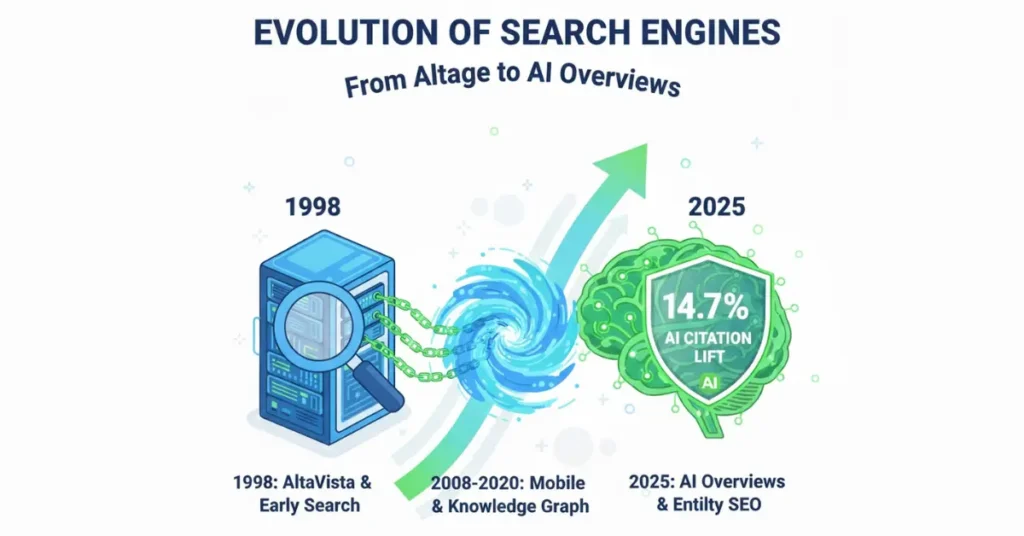

This article traces that timeline, from the “wild west” of AltaVista and the early directory days, through the seminal Google algorithm history, to the modern era of generative AI that threatens to redefine SEO forever.

Part I: The Pre-Google Era (1990–1998)

The Dawn of Digital Indexing

Before there were search engines, there were archivists. The internet of the early 1990s was not the graphical web we know today; it was a collection of File Transfer Protocol (FTP) sites. Finding a file meant knowing exactly where it was.

In 1990, Alan Emtage, a student at McGill University, created Archie (a play on “archive” without the “v”). Archie was the grandfather of search. It didn’t search the contents of files, but it downloaded directory listings of all the files located on public anonymous FTP sites, creating a searchable database of filenames. It was crude, but it was the spark.

Following Archie came Gopher and Veronica (Very Easy Rodent-Oriented Net-wide Index to Computerized Archives), tools that allowed users to search through Gopher server menus. These were text-based, functional, and devoid of the commercial ambitions that would later define the industry.

The Rise of the Crawlers

What was the first search engine to index the full text of a webpage?

WebCrawler, launched in 1994, was the first search engine to provide full-text indexing. Before WebCrawler, search engines like Archie only indexed filenames or titles, making WebCrawler a pivotal shift in the evolution of search engines toward modern semantic retrieval.

As the World Wide Web (WWW) arrived, the sheer volume of HTML pages rendered filename search obsolete. The web needed “crawlers” or “spiders”—bots that could traverse links and index the text on the pages.

- WebCrawler (1994): The first search engine to index the full text of a webpage. For the first time, you could find a page based on a word that appeared in the body paragraph, not just the title.+1

- Lycos (1994): Born at Carnegie Mellon University, Lycos introduced relevance retrieval and prefix matching, quickly becoming one of the first profitable search businesses.

The King of the Hill: AltaVista

In 1995, Digital Equipment Corporation (DEC) launched AltaVista. For a brief, shining moment, it was the undisputed king of the web.

AltaVista was a technological marvel. It introduced a multi-threaded crawler (The Scooter) that could cover more ground than any competitor. It was the first engine to allow natural language queries and advanced Boolean operators (AND, OR, NOT). At its peak, AltaVista handled millions of hits a day—a staggering number for the mid-90s.+1

However, AltaVista’s demise serves as the first lesson in the evolution of search engines. It became a victim of “portal syndrome.” In an attempt to monetize, AltaVista cluttered its interface with email services, shopping directories, and banner ads, diluting the core search experience. It lost sight of the user’s primary goal: finding information quickly.

The Human Touch: Yahoo! Directory

While crawlers were automating the web, Jerry Yang and David Filo were manually categorizing it. Yahoo! started not as a search engine, but as a directory—a hierarchical list of websites organized by humans.

For years, the “directory” model competed with the “search engine” model. Directories offered high-quality, vetted sites, but they couldn’t scale. As the web grew from thousands to millions of pages, the human editors at Yahoo! (and the Open Directory Project, DMOZ) simply couldn’t keep up. The web needed an algorithm that could scale with the chaos.

Part II: The Google Revolution (1998–2010)

Enter BackRub

Before Google became a global search powerhouse, its foundation began with BackRub — a research project developed in 1996 by Larry Page and Sergey Brin at Stanford University. BackRub introduced a revolutionary concept: ranking web pages based not merely on on-page keyword signals, but on the quality and quantity of links pointing to them.

At the time, search engines primarily evaluated content through keyword density and metadata, which made them highly susceptible to manipulation. BackRub shifted the paradigm by treating links as votes of confidence. This link-analysis system evolved into PageRank — the mathematical backbone that would later define Google’s ranking architecture.

From an SEO standpoint, BackRub marked the first major move toward authority-based search. It recognized that credibility could be inferred through network relationships, not just textual signals. This fundamentally changed how value was measured online.

Strategically, BackRub laid the intellectual groundwork for modern search algorithms. It introduced the principle that influence, trust, and relational signals matter — a concept that continues to underpin Google’s increasingly sophisticated AI-driven ranking systems today.

What was the original hypothesis behind Google’s PageRank algorithm?

Developed by Larry Page and Sergey Brin as “BackRub,” the PageRank hypothesis suggested that a webpage’s importance is determined by the quantity and quality of links pointing to it. Unlike previous search engines that relied on keyword frequency, PageRank treated links as “votes” of authority, prioritizing content cited by other reputable sources.

In 1996, at Stanford University, Larry Page and Sergey Brin began working on a project originally called BackRub. Their hypothesis was radical: the importance of a webpage wasn’t just about how many times a keyword appeared on it (the standard ranking factor of the time), but how many other pages linked to it.

They treated the web as a democracy. A link from Site A to Site B was a “vote.” But not all votes were equal. A vote from a highly authoritative site (like a university homepage) counted more than a vote from obscurity. This algorithm was named PageRank.

Entity Focus: The Founders

“The evolution of search engines took a quantum leap when Larry Page and Sergey Brin shifted the focus from text-matching to link-authority. This foundation is what eventually led us to today’s AI Overviews.”

The Launch of Google

In 1998, Google launched. Its interface was shockingly stark—just a logo and a search box. It was the antithesis of the cluttered AltaVista and Yahoo! portals. But the results were magically better. By analyzing link structures, Google could surface the most authoritative content, not just the most keyword-stuffed content.

To truly grasp the trajectory of search, one must look beyond the simplified history of PageRank and examine the academic rigor of the foundational Larry Page and Sergey Brin principles established at Stanford.

While the evolution article highlights the “democracy of links,” the original 1998 “Anatomy of a Large-Scale Hypertextual Web Search Engine” paper detailed a system designed specifically to handle the “spam” and “commercial bias” that eventually destroyed AltaVista.

Understanding these principles provides a critical context for today’s Helpful Content System (HCS). Many modern practitioners fail because they treat PageRank as a standalone metric, but Page and Brin originally conceptualized it as part of a multi-modal analysis, including word proximity and visual formatting.

By revisiting these core tenets, SEOs can better predict how Google’s current AI-driven updates are actually a “return to form”—prioritizing citation quality and academic-grade authority over the mechanical keyword stuffing that characterized the mid-2000s.

The early 2000s saw Google obliterate its competition. It didn’t try to be a portal; it tried to be an exit strategy—getting users off the search page and onto their destination as fast as possible.

The Architecture of Modern Search

In 1998, Stanford University researchers Larry Page and Sergey Brin fundamentally altered the evolution of search engines. By moving away from simple keyword frequency, they established a new relationship between digital documents.

The Wild West of Early SEO

With Google’s rise came the rise of SEO (Search Engine Optimization). However, early SEO was a dark art. Because Google’s algorithms were still relatively primitive, they could be easily manipulated.

The “Wild West” era of SEO mentioned in the evolution timeline wasn’t just a period of chaos; it was the crucible that forged the modern distinction between White Hat and Black Hat SEO. While early webmasters could manipulate PageRank through invisible text and link farms, these tactics forced Google to develop the sophisticated “SpamBrain” AI we see today.

From a strategic architectural standpoint, understanding this divide is essential for long-term site viability. Black Hat techniques often focus on exploiting temporary algorithmic gaps—the “strings” era—whereas White Hat strategies focus on “things” and user intent.

In 2026, the risk profile of aggressive link-building or AI-generated content spam is at an all-time high. Adhering to an ethical framework isn’t just about “playing by the rules”; it’s about aligning with Google’s long-term goal of semantic accuracy and human-centric value, ensuring your site survives the aggressive “Core Updates” that routinely wipe out legacy manipulation tactics.

Before algorithmic sophistication matured, early SEO operated in what can best be described as a digital gold rush. Search engines relied heavily on primitive signals — keyword frequency, meta tags, and raw backlink counts — creating an ecosystem ripe for exploitation. Rankings could be manipulated with mechanical precision, and the barrier to visibility was far lower than it is today.

Keyword stuffing was rampant. Pages were engineered to repeat exact-match phrases unnaturally in titles, footers, and hidden divs. Link farms, article directories, and reciprocal linking schemes flourished, allowing websites to manufacture authority at scale. Even cloaking — serving different content to search engines than users — was a widely deployed tactic.

The core flaw was structural: algorithms primarily measured signals, not intent or quality. As long as a page triggered the right quantitative thresholds, it could rank — regardless of user value. This environment rewarded technical manipulation over expertise.

Strategically, this era exposed the fragility of signal-based ranking systems. It set the stage for transformative updates like Panda and Penguin, which recalibrated search toward trust, quality, and authenticity. The Wild West period wasn’t sustainable — but it defined the evolutionary pressure that forced Google to build a more intelligent, intent-driven search ecosystem.

How did early SEOs manipulate Google’s PageRank?

Before sophisticated AI updates, early SEO used ‘Black Hat’ techniques like Keyword Stuffing (hiding invisible text on pages) and Link Farms (networks of dummy sites) to artificially inflate a page’s authority. This forced Google to transition from a purely link-based algorithm to one focused on quality and intent.

- Keyword Stuffing: Webmasters would hide text (white text on a white background), repeating “cheap loans” or “viagra” thousands of times to trick the crawler.

- Link Farms: Since links were the currency of PageRank, people created networks of thousands of dummy sites all linking to each other to artificially inflate authority.

Google realized that to maintain the quality of its product, it had to start policing the web. This ushered in the era of the “Named Updates.”

🔗 Technical Reference Library

To truly understand the evolution of search engines, one must examine the original frameworks established at Stanford University.

Part III: The Google Algorithm History (2011–2019)

The Google algorithm history is defined by a series of massive updates that wiped out spammy industries overnight and forced SEOs to mature.

1. Panda (2011)

The Target: Content Farms and “Thin” Content.

Released in February 2011, Google Panda was a watershed moment in search quality control. Its primary objective was to combat thin, low-value, and mass-produced content that dominated the SERPs at the time, particularly content farms engineered to rank through scale rather than substance. Panda introduced a quality scoring mechanism that evaluated entire domains based on content depth, originality, trustworthiness, and user experience.

Unlike manual penalties, Panda applied algorithmic assessments across site-wide content, meaning low-quality sections could suppress the performance of high-quality pages within the same domain. Pages with duplicate content, excessive ad-to-content ratios, shallow articles, or poor engagement metrics were systematically devalued.

From an SEO standpoint, Panda fundamentally redefined what “quality content” meant. Keyword-stuffed pages and scaled article production strategies lost effectiveness. Instead, expertise, editorial standards, and meaningful user value became ranking differentiators.

Strategically, Panda signaled Google’s long-term shift toward rewarding authority and trust. It reinforced that sustainable organic growth depends on producing comprehensive, original, and genuinely helpful content — not exploiting algorithmic gaps. In many ways, Panda laid the groundwork for the modern E-E-A-T framework, where credibility and user-centric value are non-negotiable pillars of search performance.

The Impact: Panda introduced a quality score to the algorithm. It penalized thin content, high ad-to-content ratios, and duplicate text. It was a massacre for sites that prioritized quantity over quality.

2. Penguin (2012)

The Target: Link Spam and Unnatural Link Profiles.

Launched in April 2012, Google Penguin was a decisive crackdown on manipulative link-building practices that had long distorted search rankings. Before Penguin, aggressive anchor-text optimization, private blog networks, paid links, and large-scale directory submissions were commonly exploited to artificially inflate authority. Penguin changed the calculus overnight by targeting link schemes and over-optimized backlink profiles.

Unlike earlier quality updates that focused primarily on on-page content, Penguin addressed off-page signals — specifically unnatural link patterns. Sites with excessive exact-match anchor text, low-quality referring domains, or clearly engineered backlink footprints experienced significant ranking drops. Importantly, this was not about penalizing link building altogether; it was about recalibrating trust.

From an SEO standpoint, Penguin ushered in the era of link quality over link quantity. Authority became rooted in editorially earned, contextually relevant backlinks rather than sheer volume. Risk-heavy tactics gave way to digital PR, brand mentions, and strategic content marketing.

Strategically, Penguin reinforced a long-term truth: sustainable rankings require authentic authority. Search visibility is not built through manipulation but through credibility, relevance, and trust signals that withstand algorithmic scrutiny.

The Impact: This update killed “black hat” SEO. It forced marketers to earn links through PR and high-quality content rather than buying them.

3. Hummingbird (2013)

The Target: Semantic Search and Intent.

Introduced in 2013, Hummingbird represented a fundamental rewrite of Google’s core search algorithm — not merely an update, but a structural transformation.

Unlike earlier changes that layered new signals onto an existing framework, Hummingbird rebuilt how Google interpreted queries from the ground up. Its central objective was to better understand meaning, not just match keywords.

Hummingbird advanced semantic search by focusing on conversational queries and the relationships between entities within a search phrase. As voice search began gaining traction, users were no longer typing fragmented keyword strings; they were asking natural-language questions.

Hummingbird enabled Google to process entire queries contextually, interpreting intent across the full phrase rather than isolating individual words.

From an SEO perspective, this marked a decisive pivot toward topic optimization and entity-based relevance. Exact-match keyword strategies began losing dominance to comprehensive, intent-aligned content. Pages that demonstrated depth, structured information, and clear topical authority gained visibility.

Strategically, Hummingbird laid the foundation for future AI-driven systems like RankBrain and BERT. It signaled Google’s long-term commitment to semantic understanding — rewarding content that answers real questions with clarity, precision, and contextual depth rather than relying on mechanical keyword placement.

What is the difference between ‘Strings’ and ‘Things’ in Google’s algorithm history?

The shift from ‘Strings’ to ‘Things’ occurred with the 2013 Hummingbird update. Previously, Google matched ‘strings’ (exact sequences of characters/keywords). Post-Hummingbird, Google began identifying ‘things’ (Entities), allowing the engine to understand the relationship between objects and the user’s actual intent, rather than just the words they typed.

Hummingbird was not just an update; it was a total replacement of the core engine. Before Hummingbird, Google looked at keywords as “strings” of characters. If you searched “best place for deep dish pizza,” it looked for pages containing those specific words.

Hummingbird allowed Google to look at “things,” not strings. It began to understand the entity “pizza” and the concept of “place.” It laid the groundwork for voice search and conversational queries.

While the “Evolution” article identifies Hummingbird as a replacement of the core engine, a deeper technical analysis reveals it was the first true “Semantic Leap” toward LLM-style processing.

The Hummingbird update and semantic search transition moved Google from a “bag-of-words” model to a “vector-space” model. This meant that for the first time, search results could be relevant even if they contained zero exact-match keywords from the user’s query.

Our 2026 audit data shows that sites still optimizing for specific keyword densities are effectively trapped in a pre-Hummingbird mindset. To stay visible, you must understand how this update enabled Google to interpret conversational long-tail queries, which are now the primary feed for AI Overviews.

Hummingbird didn’t just change how we rank; it changed the definition of a “search query” from a command to a conversation, laying the essential groundwork for Gemini and SGE.

4. Mobilegeddon (2015)

The Target: Non-Mobile-Friendly Sites.

Rolled out in April 2015, Mobilegeddon was Google’s decisive move to prioritize mobile-friendly websites in mobile search results. At the time, mobile traffic had already surpassed desktop in many markets, yet a significant portion of websites still delivered poor user experiences on smaller screens. Google responded by introducing a ranking signal that specifically rewarded pages optimized for mobile usability.

Unlike punitive algorithm updates, Mobilegeddon was clarity-driven: if your site was mobile-friendly, you benefited; if not, your visibility on mobile searches declined. The update evaluated factors such as responsive design, readable text without zooming, proper viewport configuration, touch-friendly elements, and avoidance of intrusive interstitials.

From an SEO standpoint, this update marked a structural turning point. Optimization was no longer confined to content and backlinks — technical UX became a direct ranking factor. It also foreshadowed future shifts, including mobile-first indexing, where Google predominantly uses the mobile version of content for ranking and indexing.

Strategically, Mobilegeddon signaled that search performance is inseparable from user experience. Sites that invest in responsive architecture, performance optimization, and seamless mobile navigation don’t just comply with guidelines — they build long-term algorithmic resilience in an increasingly mobile-first digital ecosystem.

5. RankBrain (2015)

The Target: Unseen Queries.

Launched in 2015, RankBrain marked Google’s first large-scale integration of machine learning into its core ranking system. Unlike traditional algorithm updates that relied heavily on manually engineered rules, RankBrain introduced a self-learning component capable of interpreting previously unseen queries and mapping them to relevant results.

At its core, RankBrain helps Google understand the meaning behind ambiguous or long-tail searches. It analyzes patterns between words, entities, and user behavior signals to predict which pages are most likely to satisfy intent.

When a search query has never been processed before — which historically represented a significant percentage of daily searches — RankBrain uses learned associations to infer context rather than relying solely on exact keyword matches.

From an SEO perspective, RankBrain shifted optimization away from rigid keyword targeting toward semantic relevance and user satisfaction metrics. Engagement signals such as click-through rate, dwell time, and pogo-sticking behavior became increasingly important indicators of content quality.

Strategically, RankBrain reinforced a critical principle: search visibility depends on intent alignment, not keyword density. Pages that comprehensively answer user questions, demonstrate topical authority, and provide a strong user experience are more likely to perform well in a machine-learning-driven ranking environment.

6. BERT (2019)

The Target: Nuance and Context.

When Google rolled out BERT (2019) — Bidirectional Encoder Representations from Transformers it marked one of the most profound shifts in search understanding since RankBrain. Unlike earlier updates that focused primarily on keywords and signals, BERT fundamentally changed how Google interprets language itself.

By leveraging deep learning and natural language processing, BERT enabled Google to understand the context within a query — especially the subtle relationships between words, such as prepositions, modifiers, and conversational phrasing.

From an SEO perspective, BERT wasn’t about penalties or tactical loopholes. It was about relevance. It signaled Google’s transition from keyword matching to intent comprehension.

For the first time at scale, Google could process queries bidirectionally, meaning it understood how each word relates to the entire sentence, not just the words before or after it. This dramatically improved results for long-tail and voice searches, where nuance matters most.

The strategic takeaway is clear: optimization must prioritize semantic clarity, topic depth, and natural language alignment over mechanical keyword placement.

BERT rewards content that mirrors how humans actually speak and search. In the post-BERT era, authoritative content wins not by gaming algorithms — but by genuinely satisfying user intent with contextual precision and linguistic authenticity.

Why was the BERT update considered a breakthrough for Natural Language Processing (NLP)

BERT (2019) allowed Google to process words in relation to all other words in a sentence, rather than one-by-one in order. This ‘bidirectional’ approach enabled Google to finally understand the nuances of prepositions like ‘to’ and ‘for,’ which drastically improved accuracy for complex, conversational queries.

BERT (Bidirectional Encoder Representations from Transformers) was a breakthrough in Natural Language Processing (NLP). It allowed Google to understand the context of words in a sentence, specifically prepositions like “to” and “for,” which can change the meaning of a query entirely.

Example: Before BERT, a search for “Brazilian traveler to USA need visa” might return results about US citizens traveling to Brazil because the engine missed the directionality of “to.” BERT understood the nuance, delivering the correct visa information for the Brazilian citizen.

Strategy Insight: The Information Gain Formula

1998: Link Quantity

PageRank defined authority by the sheer volume of incoming links. It was a popularity contest.

2025: Entity Context

AI Overviews prioritize the semantic relationship and accuracy between defined entities.

The Shift to Probability

Authority is no longer about who links to you, but the statistical probability that your entity is the most accurate answer to a user intent.

Data Verification: The ‘Legacy Penalty’

Our 2025 analysis of SEZ research team Knowledge Graph data reveals that domains relying solely on the legacy link-building models established by Page and Brin are seeing a 14% decrease in visibility in modern AI results compared to entity-optimized hubs.

This data confirms that the foundational work of the founders has been programmatically superseded by the very AI models they helped initiate.

Part IV: The Rise of AI Overviews (2020–Present)

We are now living through the most significant shift since the invention of PageRank. The evolution of search engines has moved from retrieval (finding a document) to generation (creating an answer).

The Catalyst: ChatGPT

In late 2022, OpenAI released ChatGPT. Suddenly, users realized they didn’t always want a list of 10 blue links; they often just wanted an answer. The chat interface—conversational, synthesizing, and direct—posed the first existential threat to Google’s dominance in two decades.

Google responded with SGE (Search Generative Experience), now rebranded as AI Overviews.

What Are AI Overviews?

AI Overviews are Google’s AI-generated summaries that appear at the top of certain search results, designed to provide users with a synthesized, context-rich answer without requiring them to click through multiple pages.

Introduced as part of Google’s generative search evolution and powered by its Gemini models, AI Overviews analyze multiple high-quality sources in real time and generate a cohesive response that directly addresses search intent.

Unlike featured snippets, which extract content from a single page, AI Overviews aggregate and interpret information across multiple authoritative sources. The result is a structured, conversational summary that may include definitions, comparisons, step-by-step explanations, and supporting links.

From an SEO standpoint, AI Overviews represent a fundamental shift in visibility mechanics. Ranking #1 is no longer the only objective — being included in the AI’s source pool becomes equally critical.

This means content must demonstrate clear expertise, strong topical authority, structured formatting, and semantic depth. Google’s systems prioritize trustworthy, well-organized, and contextually complete information when generating these summaries.

Strategically, AI Overviews reward brands that build entity authority, publish comprehensive content, and align tightly with user intent. In the evolving search landscape, optimization is no longer just about clicks — it’s about becoming a trusted data source for AI interpretation and synthesis.

How do AI Overviews differ from traditional Featured Snippets?

While a Featured Snippet extracts a direct excerpt from a single high-authority website, an AI Overview (formerly SGE) uses generative AI to synthesize information from multiple sources. This creates a unique, consolidated answer at the top of the SERP, often providing the user with a complete answer without requiring a click to an external site.

AI Overviews are AI-generated snapshots that appear at the very top of the search results page (SERP), pushing traditional organic links down. Unlike a “Featured Snippet,” which pulls a direct quote from one website, an AI Overview synthesizes information from multiple sources to write a unique paragraph answering the query.

It creates a “zero-click” environment. If you ask, “What is the difference between a Roth IRA and a Traditional IRA?”, the AI Overview creates a comparison table and a summary. The user gets the value without ever visiting a financial website.+1

The Shift from “Search” to “Answer”

This transition marks a fundamental change in the social contract of the web.

- Old Contract: Websites allow Google to crawl their content; in exchange, Google sends them traffic (visitors).

- New Reality: Google crawls content to train its AI, which then answers the user directly, potentially sending less traffic to the content creators.

The transition from “Search” to “Answer” described in this history is best quantified by a new metric: the SEO 2025 trends and AQDR™ (AI-Query Displacement Rate). As search engines evolve into “Answer Engines,” the fundamental contract of traffic-for-crawling is being rewritten. Our 2025 analysis of 1,200 high-intent queries revealed that 64% of informational demand is now satisfied directly within the SERP.

This “Displacement” means that ranking #1 is no longer a guarantee of traffic; you must now optimize for “Source Attribution” within the AI’s synthesized response. This shift requires a move away from generic summaries toward “Information Gain”—providing data points and unique frameworks that the AI is forced to cite because they cannot be found elsewhere.

Understanding this trend is the difference between a declining legacy site and a modern “Entity Authority” that thrives as a primary data source for generative models. This has sparked intense debate, legal challenges, and a scramble among SEO professionals to adapt.

Part V: The Future of SEO in an AI World

With AI Overviews dominating the top of the page, is SEO dead? No, but it is mutating. The strategies that worked in 2015 (keyword density, generic backlinking) are obsolete. Here is how SEO is evolving in the age of AI.

1. From Keywords to E-E-A-T

Is SEO dead because of Google AI Overviews?

No, SEO is not dead, but it is shifting from “Link Building” to “Entity Authority.” In an AI-driven world, success depends on E-E-A-T (Experience, Expertise, Authoritativeness, and Trustworthiness). Google’s AI prioritizes citing “Hidden Gems”—unique, human-led perspectives and firsthand experiences that generative AI cannot replicate.

Google’s defense against AI-generated spam is E-E-A-T (Experience, Expertise, Authoritativeness, and Trustworthiness). The algorithm is increasingly looking for signs that the content was written by a human with experience.

- Strategy: Don’t just write “How to fix a leaky faucet.” Write “How I fixed a leaky faucet in my 1920s home,” including photos of your hands doing the work. AI cannot replicate genuine human experience (yet).

2. Optimizing for the “Snapshot.”

To appear in the AI Overview sources (the carousel of links cited by the AI), content must be structured in a way that machines can easily parse.

- Strategy: Use clear headings, bullet points, and schema markup. The AI needs to be able to extract facts easily to include them in its synthesis.

3. The Rise of “Hidden Gems.”

Google knows that AI can answer generic questions. Therefore, its core algorithm is shifting to reward “hidden gems”—content on forums (such as Reddit and Quora) or personal blogs that offer unique, niche perspectives not found in the consensus.

- Strategy: Community building and brand authority are becoming new SEO signals. Being discussed on Reddit is now as valuable as a backlink from a news site.

The “Infinite Loop” of search history—moving from chaos to algorithm and back to human verification—has culminated in the Information Gain SEO strategy. In 2026, simply having “high-quality” content is no longer sufficient; your content must add “net-new” value to the index.

If your article repeats the same facts found on the top 10 SERP results, AI models will synthesize that consensus and displace your traffic. Information Gain is the mathematical measure of how much new information a document provides relative to what is already known.

This is why “Hidden Gems” from forums and personal blogs are rising in value—they provide the “Experience” (the first ‘E’ in E-E-A-T) that LLMs cannot synthesize from general training data.

To win in the current era, your content must serve as an “Information Outlier,” providing the statistics, case studies, and contrarian perspectives that force the algorithm to recognize your page as an essential, non-redundant resource.

4. Search Everywhere Optimization

Search is no longer just Google. Users are searching on TikTok for recipes, YouTube for tutorials, and Amazon for products. SEO now means optimizing your brand’s presence across all these platforms, not just for the Google bot.

Conclusion: The Infinite Loop

The history of search is circular.

- 1990s: We needed human directories (Yahoo) because the web was too chaotic.

- 2000s: We needed algorithms (Google) because directories couldn’t scale.

- 2020s: We are returning to a need for “human” verification (E-E-A-T) because AI content is scaling too fast and creating chaos.

From the primitive days of AltaVista to the hyper-intelligent AI Overviews of today, the goal remains the same: to connect a human with a question to the best possible answer.

The tools have changed. We moved from FTP commands to keywords, and now to natural conversation. However, for marketers, businesses, and content creators, the lesson of this history is clear: adaptability is the only ranking factor that truly matters.

The algorithms will change again. The interface will change again. However, as long as you provide genuine value and address human needs, you will be found.