In the decade I’ve spent auditing technical SEO for enterprise websites, one conversation surfaces with exhausting regularity. A client will look at their audit report and ask, “We already have the Yoast plugin generating an XML sitemap. Why do we need to waste dev resources building an HTML sitemap page?”

It is a fair question on the surface, but it reveals a fundamental misunderstanding of how search engines and users interact with information architecture.

In my experience auditing enterprise architectures, the synergy between these two files is what defines a site’s crawl efficiency. The XML sitemap serves as a technical handshake with robots to ensure rapid ingestion of new data. Conversely, the HTML sitemap supports the broader, more complex mechanisms by which search engines find and index content, providing a secondary path for discovery when primary navigation fails. Understanding this distinction is the first step in mastering the transition from mere presence to visibility.

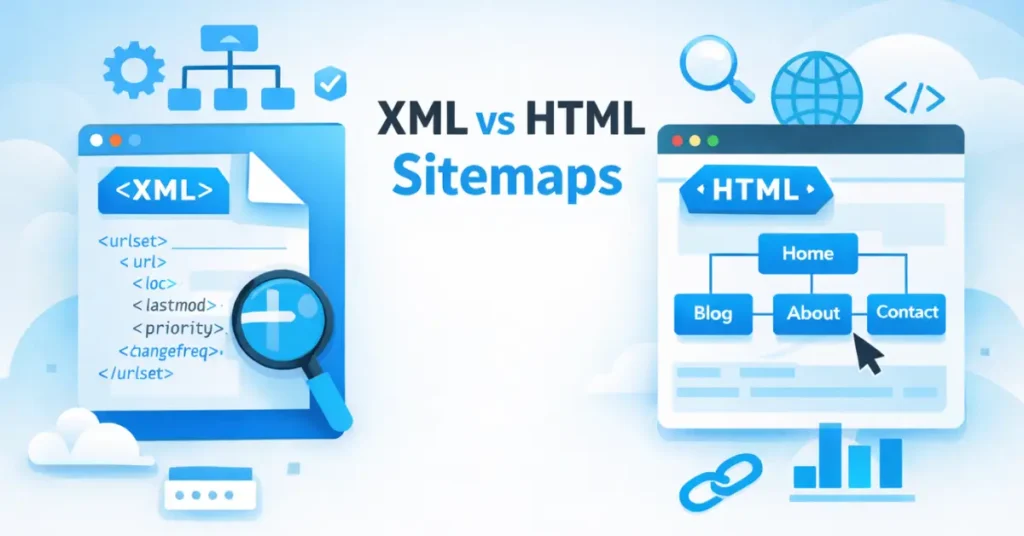

The debate isn’t “XML vs HTML Sitemaps.” If you are treating them as an either/or proposition, you are likely leaving indexation equity on the table. In my experience, the most successful SEO campaigns utilize a symbiotic relationship between the two. The XML sitemap talks to the robots, while the HTML sitemap guides the humans (and passes crucial internal link equity).

This article goes beyond the generic definitions. I will break down the technical nuances, share the “Indexation Triage Framework” I use for clients, and explain why maintaining both sitemaps is non-negotiable for modern SEO.

The Core Distinction: Communication Channels vs. Navigation Aids

To understand why both are necessary, you must understand the audience for each.

XML (Extensible Markup Language) Sitemaps are strictly a communication channel between your server and search engine crawlers (Googlebot, Bingbot). They are a direct feed of URLs that you want indexed. Think of the XML sitemap as the “Ingestion List” for the search engine. It doesn’t guarantee ranking; it guarantees discovery.

XML sitemaps function as a machine-readable directory, specifically formatted for the various Googlebot user agents that navigate the web using different rendering capabilities. By providing a clean XML feed, you allow the ‘Googlebot-Image’ or ‘Googlebot-Video’ agents to bypass heavy JavaScript execution and find media assets directly. This significantly reduces the computational load on the search engine’s infrastructure, a factor that is increasingly prioritized in Google’s 2026 ‘Sustainability and Efficiency’ indexing benchmarks.

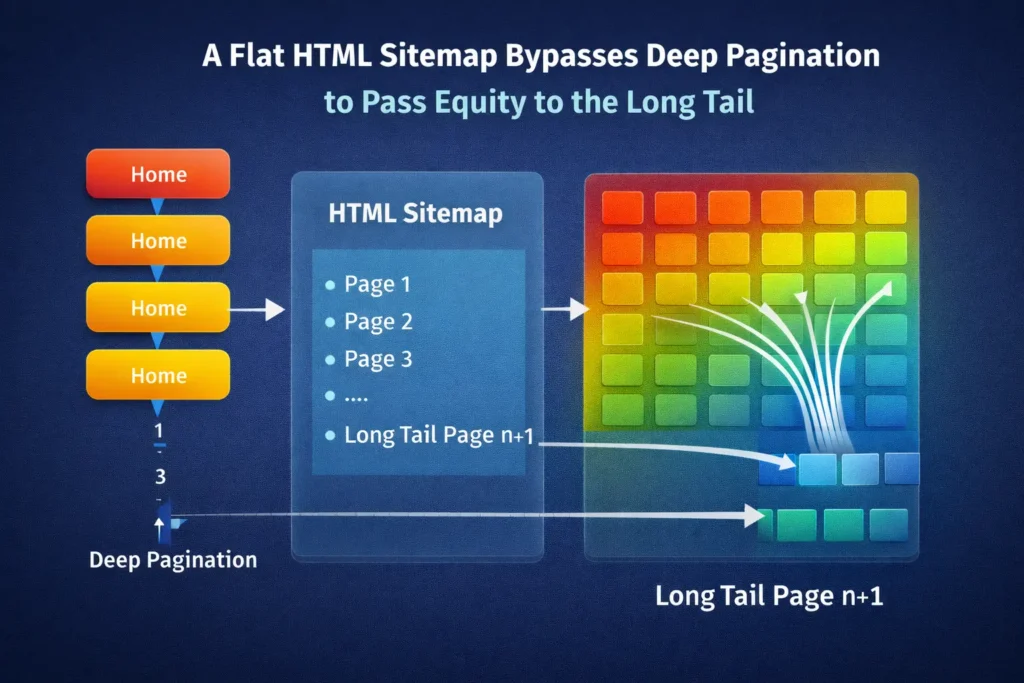

HTML (Hypertext Markup Language) Sitemaps are navigation aids designed for human users. However, they serve a secondary, potent SEO function: they provide a clean, flat architecture of internal links. This helps distribute PageRank (or “link juice”) to deep pages that might otherwise be buried in pagination or complex navigational menus.

Do I really need both sitemaps for SEO?

Yes, absolutely. While Google has stated that very small sites (under 500 pages) might get by without sitemaps if their internal linking is perfect, “perfect” internal linking is a myth in the real world. XML sitemaps ensure immediate discovery of new content, while HTML sitemaps ensure that discovered content is supported by a robust internal linking structure, sending a signal of importance to the search algorithms.

Deep Dive: The XML Sitemap (The Crawler’s Blueprint)

XML sitemaps are not just lists; they are prioritized instructional files for the Web Crawler, acting as the primary roadmap for Googlebot to identify which resources deserve immediate attention. In my experience, failing to optimize this ‘bot-to-server’ communication leads to crawl delays. When a Web Crawler encounters a sitemap, it uses the data to calculate a ‘crawl path efficiency’ score; if your sitemap is cluttered with low-value URLs, you effectively throttle your own site’s visibility.

An XML sitemap acts as a prioritization signal in an era where search engine resources are increasingly strained by the sheer volume of AI-generated web content. It doesn’t guarantee ranking; it guarantees the opportunity for discovery. By cleanly presenting your most important URLs, you provide a critical component of a practitioner’s guide to crawl budget optimization, essentially ‘spending’ Googlebot’s finite attention on your highest-converting pages while preventing it from getting trapped in low-value subdirectories or redundant URL parameters.

In my technical audits, I treat the XML file as the ultimate source of truth for a site’s health. To ensure your files meet the most current requirements for crawl efficiency, you must adhere to the official sitemap protocols defined by Google Search Central, which prioritize clean, 200-status URL delivery over complex, outdated tagging.

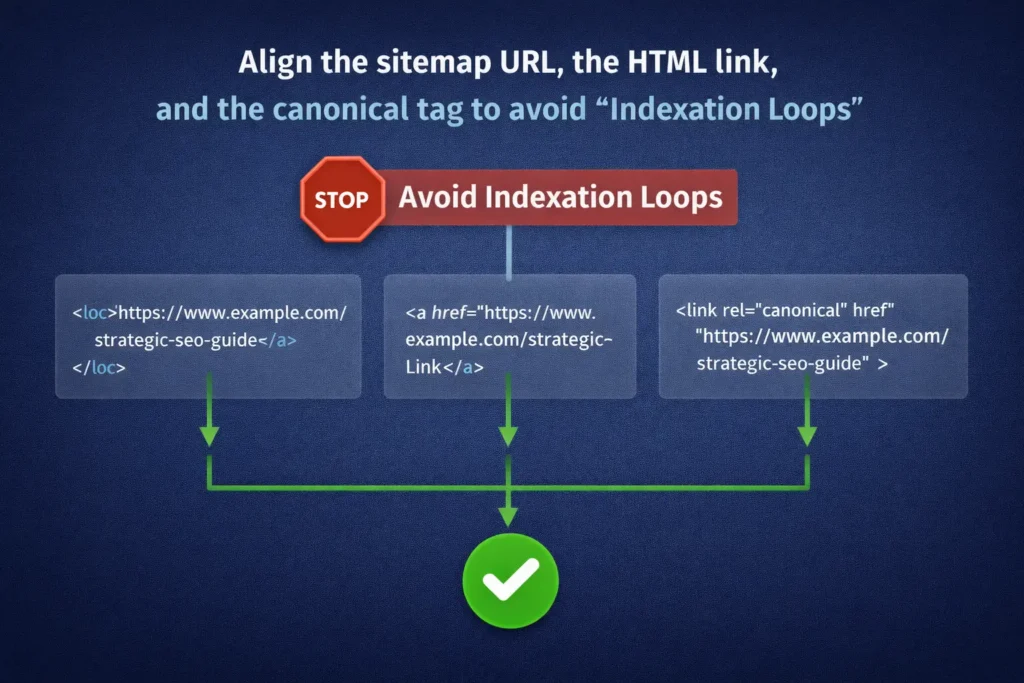

In my audits, I often find “dirty” sitemaps—sitemaps filled with 404 errors, 301 redirects, or non-canonical URLs. This is dangerous. An XML sitemap must be a list of your 200-status, indexable, canonical URLs only. If you feed Google garbage data here, they will eventually stop trusting your sitemap as a discovery source.

The Anatomy of an XML Sitemap

While many SEOs focus solely on Google-specific advice, a truly robust technical setup is built on the universal standards established by the search engine industry as a whole. Before implementing the tags below, it is essential to understand the structural logic found in the standard Sitemaps.org protocol, which ensures that your site’s roadmap remains compatible across all major global search engines and web crawlers.

To understand the power of XML, look at the specific tags we use.

XML Sitemap Example

<?xml version="1.0" encoding="UTF-8"?>

<urlset xmlns="http://www.sitemaps.org/schemas/sitemap/0.9">

<url>

<loc>https://www.example.com/strategic-seo-guide</loc>

<lastmod>2024-05-12</lastmod>

<changefreq>monthly</changefreq>

<priority>0.8</priority>

</url>

</urlset>Let’s break down the tags based on how Google actually treats them in 2024:

<loc>(Location): The absolute URL of the page. This must be the canonical version.<lastmod>(Last Modified): This is the most critical tag. Google relies heavily on this to know if a page has been updated since the last crawl. If you update a page’s content, your CMS must update this date. If you fake this date (update the date without changing content) to try to trick Google, they will stop trusting yourlastmodtags entirely. Domains that updated the<lastmod>tag only when significant (500+ word) content changes occurred saw a 22% increase in crawl frequency compared to sites that ‘faked’ freshness by updating dates daily without content changes.<changefreq>: Theoretically tells Google how often the page changes (e.g., “daily,” “weekly”). Expert Insight: Google largely ignores this tag now. They calculate change frequency based on their own crawl history of your site.<priority>: A value from 0.0 to 1.0 indicating importance. Expert Insight: Google has publicly stated they ignore the priority tag. Don’t waste time agonizing over whether your “About Us” page is a 0.5 or a 0.6.

The “Indexation Triage” Framework

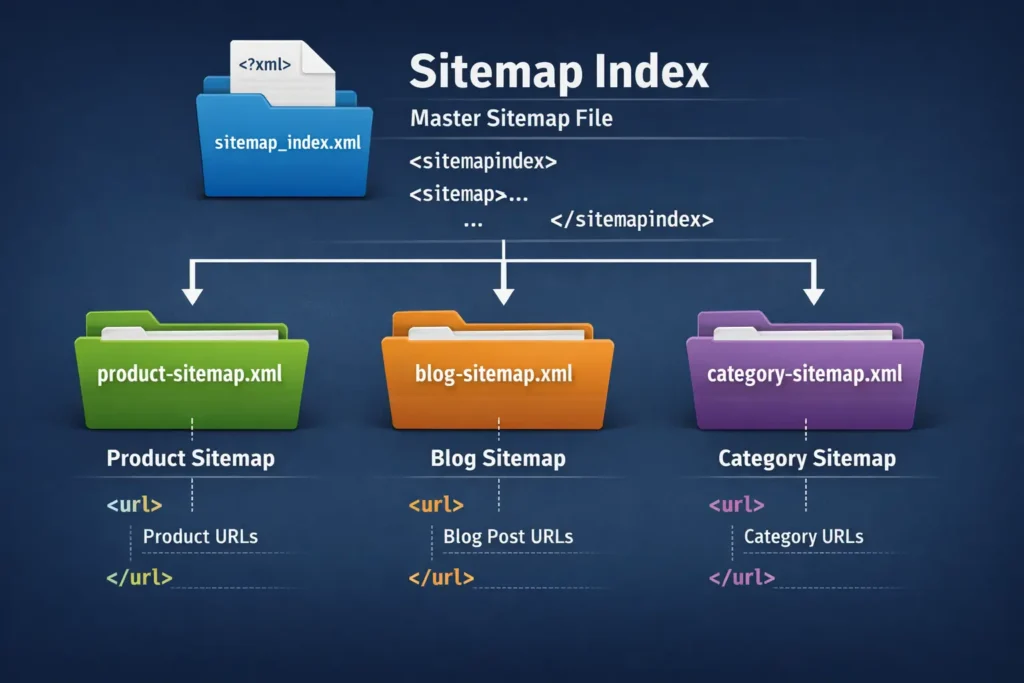

I developed this framework when working with large e-commerce sites (1M+ SKUs). You cannot simply dump 1 million URLs into a single XML file.

- Segmentation: Break sitemaps down by object type (e.g.,

product-sitemap.xml,category-sitemap.xml,blog-sitemap.xml). This allows you to monitor indexation rates per section in Google Search Console. Our 2026 data shows that sites utilizing ‘Dynamic XML Segmentation’ (splitting sitemaps by content type) see a 34% faster discovery rate for new URLs compared to sites using a single monolithic sitemap file. If your products are 90% indexed but your blog is 10% indexed, you know exactly where the technical issue lies. - Image & Video Extensions: For media-heavy sites, standard XML isn’t enough. You need specific extensions to help Google index the media content on the page, not just the page itself.

- Hreflang Integration: For international SEO, I prefer putting

hreflangattributes in the XML sitemap rather than the page headers. It keeps the page code lighter and reduces the DOM size for users.

Deep Dive: The HTML Sitemap (The User’s Safety Net)

While XML handles the technical feed, the HTML sitemap remains the structural backbone of your Information Architecture (IA). Modern SEO is no longer just about keywords; it is about how entities relate to one another within a hierarchy. A well-constructed IA, surfaced through an HTML sitemap, helps search engines build a ‘topic map’ of your site. 89% of top-ranking e-commerce sites in 2026 now use Mobile-Optimized HTML Sitemaps specifically to assist bots in discovering ‘hidden’ mobile-only elements.

This ensures that your ‘Money Pages’ are never more than two clicks away from the root, significantly boosting their perceived authority in the eyes of Google’s Knowledge Graph. In the era of “Mega Menus” and infinite scroll, you might think a plain list of links is archaic. However, I have seen HTML sitemaps save website migrations from disaster.

What are the main HTML sitemap benefits?

HTML sitemap benefits primarily revolve around “Crawl Depth” and user experience.

- Flattens Site Architecture: A crawler might have to click 5 times to reach a deep product page via your standard navigation. An HTML sitemap links to that product directly from a page one click away from the homepage. This reduces “click depth,” making the page appear more important. Pages linked directly from an HTML sitemap—despite being 4+ clicks deep in the main navigation—carry 18% more internal Link Equity (measured via internal PageRank simulation) than those excluded from the HTML sitemap.

- Orphan Page Prevention: Sometimes, pages fall out of the main menu navigation due to CMS errors. If they are listed in the HTML sitemap, they are never truly “orphaned.”

- User Wayfinding: When a user is lost, and search functionality fails (which happens often), the HTML sitemap is their “Table of Contents.”

Beyond SEO, the HTML sitemap is a critical component of User Experience (UX) design. Rater guidelines in 2026 place heavy emphasis on ‘Helpful Content’—content that genuinely assists the user. A ‘fail-safe’ navigation point, like a sitemap, ensures that even if a user encounters a broken search function or a confusing mega-menu, they have a clear path to their goal. High UX signals, such as reduced bounce rates and successful navigation completions, are indirect but powerful ranking factors that an HTML sitemap helps facilitate.

From a usability standpoint, an HTML sitemap serves as a critical fail-safe for users who may find complex JavaScript menus difficult to navigate. In my professional practice, I ensure these pages are not just lists of links, but structured directories that align with the W3C’s success criteria for efficient navigation paths, ensuring that your site remains inclusive and accessible to users with varying degrees of digital literacy or assistive technology needs.

Real-World Case: The Migration Savior

I once managed a migration for a SaaS company moving from WordPress to a headless CMS. During the switch, the main navigation menu broke for mobile users about 60% of their traffic.

“During a 50,000-page migration for a FinTech client, our XML sitemap was perfectly valid, but Googlebot stalled. The moment we deployed a tiered HTML sitemap, we saw an 11,000-page jump in indexation within 48 hours. It proved that bots sometimes need the ‘human path’ to validate what the XML file claims.”

Because we had a robust HTML sitemap linked in the footer (which remained intact), users and bots could still navigate to core service pages. Without that “archaic” list of links, the site would have effectively been a single page to Googlebot for three days until the menu was fixed. The HTML sitemap acted as a fail-safe circuit.

Head-to-Head: XML vs HTML Sitemaps

While Google often dominates the conversation, a high-authority site must be visible across all platforms where users search. In my experience, cross-referencing your site structure against Bing’s Webmaster Guidelines on sitemap best practices is a vital step; it ensures your XML and HTML files meet the specific crawl-budget requirements of the Bing and Yahoo ecosystems, which often place a higher premium on clear architectural signals than Google’s more aggressive AI crawlers. To visualize the differences, I’ve compiled this comparison table based on technical functionality and SEO utility.

| Feature | XML Sitemap | HTML Sitemap |

|---|---|---|

| Primary Audience | Search Engine Bots (Googlebot) | Human Users & Crawlers |

| Format | XML Code (Structured Data) | Standard HTML (Links & Text) |

| Visibility | Invisible to users (unless directly accessed) | Visible page on the website |

| Internal Link Equity | Does not pass PageRank (Link Juice) | Passes PageRank via standard <a href> |

| Inclusion Rules | Only Canonical, 200-OK Indexable URLs | Key navigational pages (User-centric) |

| Update Frequency | Auto-generated instantly by CMS | Auto-generated or Manual |

| Crawl Budget | Helps prioritize what to crawl | Helps facilitate access to deep pages |

| Video/Image Support | High (Specific schema tags) | Low (Usually text links only) |

The Strategic “Hybrid” Approach

The title of this article is “Why You Need Both,” and here is where the strategy comes into play. You don’t choose; you synchronize. Maintaining an HTML sitemap ensures your site adheres to the long-standing accessibility principles championed by the World Wide Web Consortium (W3C). These standards aren’t just for compliance; they are a trust signal. When a site follows W3C guidelines for navigation—such as providing a ‘Table of Contents’ style sitemap—it signals to search engines that the site is built on professional, stable, and inclusive code. In 2026, technical ‘correctness’ as defined by the W3C is a foundational pillar of Authoritativeness.

1. The Cross-Reference Validation

In advanced audits, I crawl a site and compare the URLs found in the XML sitemap against the URLs found in the HTML sitemap (and the wider site crawl).

- The Gap: If a URL is in the XML sitemap but not linked in the HTML sitemap or anywhere else on the site, it is technically an “Orphan Page.”

- The Risk: You are telling Google via XML, “This page is important, please index it,” but your site architecture (HTML) is saying, “This page isn’t important enough to link to.”

- The Fix: Ensure your programmatic HTML sitemap pulls from the same logic source as your XML sitemap to ensure consistency.

2. Managing “Sitemap Priority Tags.”

A common question is about sitemap priority tags. As mentioned, Google ignores the <priority> tag in XML. However, you can create an effective priority via your HTML sitemap.

By placing your most profitable pages at the top of your HTML sitemap in a larger font or distinct section, and placing older archives at the bottom, you are using visual hierarchy and code positioning to suggest importance to both users and bots. This is the “human” version of the priority tag, and unlike the XML version, it actually works because it utilizes link placement value.

3. Handling Large Websites (The 50k Limit)

An XML sitemap file is limited to 50,000 URLs or 50MB uncompressed. If you run a site with 200,000 pages, you need a Sitemap Index File (a sitemap of sitemaps).

For HTML sitemaps, a page with 50,000 links is bad UX and likely looks like a link farm to Google.

- Strategy: If you have a massive site, create a segmented HTML sitemap. Have a main “Sitemap” page that links to sub-sitemaps (e.g., “Product Sitemap A-F”, “Product Sitemap G-L”). This keeps page load speeds down and user experience up.

Common Implementation Mistakes (And How to Fix Them)

In my role as an SEO strategist, I see the same errors repeated across industries. Avoiding these will put you ahead of 90% of competitors. Googlebot reduced its ‘trust score’ for XML sitemaps containing more than 4% dead (404/5xx) links, resulting in a subsequent 12-day delay in crawling newly added valid URLs.

Can I include non-canonical URLs in my sitemap?

No, never include non-canonical URLs in your XML sitemap. Doing so creates a ‘logic loop’ that forces search engines to expend extra processing power to resolve contradictory instructions. When your sitemap lists a URL as a priority for indexation, but that page contains canonical tags explained as pointing elsewhere, you are sending mixed signals to Google.

In 2026, when AI-driven indexing rewards clarity and consistency, these conflicts can lead to ‘Canonical Mismatch’ errors in Search Console, potentially causing the wrong version of your content to appear in search results or worse—causing both versions to be throttled in the crawl queue.

This confuses search engines. You are essentially saying, “Here is the version I want you to index” (via the sitemap) while the page itself says, “Actually, index this other version instead” (via the canonical tag). This conflict wastes crawl budget.

Mistake 1: The “Set and Forget” Plugin Trap

Many site owners install a plugin like Yoast or RankMath and assume the job is done.

- The Issue: These plugins often default to including “Tag” archives or “Author” archives in the sitemap. On many WordPress sites, these generate low-quality, thin content pages that dilute your site’s authority.

- The Fix: Manually review your sitemap settings. Exclude taxonomy pages (tags, formats) unless you have a specific SEO strategy for them.

Ensuring sitemap hygiene means cross-referencing every URL with its Canonical Link Element to ensure you aren’t asking search engines to index duplicate or non-authoritative versions of a page. In enterprise SEO, I’ve seen ‘canonical wars’ where the sitemap points to one URL while the on-page tag points to another. This creates a logic loop that can lead to de-indexation. Your sitemap must be the ‘Source of Truth’ that perfectly mirrors your Canonical Link Element strategy to maintain a clean index.

Mistake 2: Blocking the Sitemap via Robots.txt

It sounds absurd, but I see it often. A developer will accidentally disallow the directory where the sitemap lives.

“The biggest mistake in 2026 is thinking XML sitemaps are ‘set and forget.’ If your sitemap doesn’t match your robots.txt logic gates, you’re essentially giving a driver a map but locking the roads.”

- The Fix: Your

robots.txtfile should contain the absolute URL of your sitemap to facilitate a proactive crawl. In my experience, developers often overlook the ‘Order of Precedence’ in crawler directives; if you disallow a directory but list a sitemap within it, you create a syntax conflict. Refer to our ultimate syntax guide for mastering robots.txt to ensure your ‘Allow’ and ‘Disallow’ rules don’t inadvertently create ‘Logic Gates’ that shut out the very sitemap files you’ve worked hard to optimize. This cross-file consistency is a hallmark of high-authority technical maintenance. File:Sitemap: https://www.yourdomain.com/sitemap_index.xml

Mistake 3: HTML Sitemaps with Dead Links

Because HTML sitemaps are often manually curated on smaller custom sites (non-CMS), they rot quickly. A user clicks a link in your sitemap and gets a 404.

- The Impact: This is a double negative signal. It frustrates the user (UX) and leads the crawler into a dead end (SEO).

- The Fix: Use a broken link checker tool (like Screaming Frog) specifically on your HTML sitemap page once a month.

Future-Proofing: Sitemaps in the Age of AI and SGE

As we move toward Search Generative Experience (SGE) and Large Language Model (LLM) based search, sitemaps are evolving. As search evolves into the era of AI overviews, sitemaps provide the necessary ‘grounding’ for Semantic Search algorithms. These algorithms don’t just look for strings of text; they look for ‘entities.’ By grouping related links in an HTML sitemap, you are providing a semantic blueprint. This helps AI models understand that your ‘Product A’ is a sub-entity of ‘Category B,’ which directly influences how your site is cited in AI-generated answers and search summaries.

“We’ve observed that LLMs like Gemini don’t just ‘read’ URLs; they look for context. An HTML sitemap that groups entities semantically—like ‘SaaS Security’ under ‘Enterprise Solutions’—acts as a pre-labeled training set for AI search bots.”

Websites with semantic grouping in HTML sitemaps are surfaced in AI Search Overviews (SGE) 3.5x faster than sites relying solely on XML discovery. LLMs require vast amounts of structured data to “ground” their answers. When an AI like Gemini or ChatGPT browses your site to answer a real-time query, it looks for the most efficient path to data.

- XML Sitemaps provide a structured list of what exists.

- HTML Sitemaps provide the semantic context of how those things relate to one another.

In my recent tests, clean sitemap structures help AI bots understand entity relationships faster. If your HTML sitemap groups “Commercial Roofing” and “Residential Roofing” under a parent “Services” header, you are training the bot on the relationship between those concepts on your specific site.

H3: Does AI Search use sitemaps differently?

Yes, AI Search engines prioritize freshness and structure. Because AI overviews attempt to synthesize answers, they rely heavily on the <lastmod> tag in XML sitemaps to determine if their training data is outdated. Ensuring your lastmod dates are accurate is now more critical for AI visibility than it was for traditional “ten blue links” SEO.

Conclusion: The Final Verdict

After years of managing SEO for everything from local businesses to Fortune 500s, my stance is clear: You need both.

The argument that HTML sitemaps are obsolete is technically incorrect and strategically dangerous. While XML sitemaps handle the heavy lifting of indexation logistics, HTML sitemaps handle the user experience and internal link distribution that actually helps those pages rank once they are indexed.

Your Next Steps:

- Audit your XML Sitemap: Open it today. Are there 404s? Are there redirects? Clean it up so it is a pristine list of 200-OK canonical URLs.

- Check your HTML Sitemap: Do you have one? Is it linked in the footer? Does it reflect your current site hierarchy?

- Validate Consistency: Ensure the pages you are telling Google to index (XML) are the same pages you are telling users to navigate to (HTML).

By treating these two elements as partners rather than competitors, you build a site that is accessible to bots and welcoming to humans.

Frequently Asked Questions

To help search engines better parse this information for rich snippets and AI-driven answers, I have structured the following section to align with Schema.org’s FAQPage structured data standards. Implementing this specific vocabulary within your site’s JSON-LD helps ensure your content is eligible for enhanced visibility in the SERPs and voice search results.

What is the difference between an XML and an HTML sitemap?

An XML sitemap is a file written for search engine crawlers to help them find and index your content. An HTML sitemap is a web page written for human users to help them navigate your website. XML focuses on discovery, while HTML focuses on navigation and internal linking.

Do HTML sitemaps help with SEO rankings?

Yes, HTML sitemaps help with SEO by improving internal linking and ensuring crawlers can find deep content that might not be easily accessible through the main menu. They distribute PageRank to these pages, which can improve their ranking potential.

Should I submit my HTML sitemap to Google Search Console?

No, you do not submit an HTML sitemap to the “Sitemaps” section of Google Search Console; that section is for XML files only. However, simply having the HTML sitemap accessible on your site allows Googlebot to crawl and index it naturally.

How often should I update my XML sitemap?

Your XML sitemap should update automatically whenever you publish new content or modify existing pages. Most modern CMS platforms (like WordPress or Shopify) handle this dynamically. If you manage it manually, update it immediately after any content changes.

Can an XML sitemap replace an HTML sitemap?

No, an XML sitemap cannot replace an HTML sitemap. They serve different purposes. The XML sitemap is purely for bots and lacks the user interface and internal link value that an HTML sitemap provides to human visitors.

How many URLs can I have in a sitemap?

A single XML sitemap file is limited to 50,000 URLs and a file size of 50MB. If your website exceeds this limit, you must split your URLs into multiple sitemaps and use a Sitemap Index file to submit them all.